Some collectors go to great lengths to acquire very early material in their field. They seek out early or earliest versions of important material. There is the pleasure of the hunt. But there are reasons that have to do with the subject area of the collection itself. Early editions illuminate the history or even pre-history of the subject being collected.

Think for example of postal history, or first editions of books. You can think of many more. But this is about photography.

I’ll devote a future Newsletter to issues related to the different published versions of small format photographs on mounts, such as CDV’s, stereo views and Cabinet Cards, where virtually the same or very similar prints will appear on different mounts. Many collectors will prize the earliest edition of such a photograph, even if it is only indicated by the mount and not the photograph itself. Here I want to make some comments on the larger photographic print.

For most film-based photography, the earliest “version” is the negative. Oddly, there is relatively little collecting interest in negatives in general. In just a few cases the negative has an independent status as an art object. This is particularly the case of paper and waxed paper negatives of calotypes, but not yet of glass or film negatives.

Some negatives have importance in revealing the evolution of the photograph from the instant the camera shutter is opened to the final print. There is recent welcome interest in the contact sheet, that reveals the “behind the scenes” context of a particular image. Sarah Greenough’s work with Robert Frank’s contact sheets and the organization of the pictures in “The Americans” is a great recent example.

Film-based photography followed changes in cameras, enlargers, negative material, processes and printing paper. Of particular interest in the case of paper prints are the changes in paper and printing processes, as these, along with the skill and vision of the printer, determine the sensuous character of the final print.

“Vintage” is a loosely used term. An experienced collector will often be able to tell, even at a distance, if a certain gelatin silver print looks like it might be from the 1920’s, ‘30’, 40’s, or 50’s. Many “printed later” prints will just look wrong to one accustomed to seeing earlier prints.

Starting with the 1970’s, it will be much more difficult to tell on superficial examination whether a print is from the ‘70’s or the ‘80’s. One has become accustomed to black lighting certain prints to get a clue if a print might have been made before, say, 1945, or definitely later.

At the great 2010 exhibition at MOMA of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, I was awed by the beauty of the early prints— their tones, the way they lay on the paper. Once I got into the later prints I found a similarity to most of them. They were matted so one could not see the margins nor was there any information about what was on the verso. This presentation was in accordance with C-B’s own aesthetic that placed the greatest importance on the picture as a record of an instant in time, and not so much on the character of the print.

In the last Be-hold auction, a print was offered of Cartier-Bresson’s popular image “Bords de la Marne” [“On the Banks of the Marne”] I noted (and included a scan of) the stamps and notations on the verso. This was a later print of the 1930’s picture. I described the heavy Agfa paper and its “pearl” surface that reminded me of the true vintage prints. There were some slight bends from handling but no damage to the surface. [This type of condition is easily dealt with by standard conservation.] It had a starting bid [reserve] of $2000, but didn’t get any bids.

In the great Sotheby’s sale of 11 December 2014, “175 Masterworks To Celebrate 175 Years Of Photography,” there was a print of the same picture from the 1950’s. That had important provenance, and was enhanced by being part of this historic auction. It sold for $53,125. Neither print was signed.

I am still puzzled by the huge disparity between the fate of the two Cartier-Bresson prints auctioned within a month of each other

The Sotheby’s result, however, was partly significant in that it showed that the character of the print (along with the provenance) could generate far more collecting excitement than just a signature. Indeed looking up the auction records for this picture, one finds numerous later prints, signed, and with various stamps and notations, some in the range of $10,000 to almost $15000. Many of these “printed later” prints had the generic “modern” gelatin silver look.

A signed photograph by itself denotes a “lifetime” print, distinct from later prints made from a negative or copy negative after the death of the photographer. However there are some prints made by some photographers that are “early” or even “vintage” that are not signed, that have the special character of a vintage print that should be appreciated and valued.

Many photographers will sign wholesale a great number of prints that were in fact printed by someone else. This could be a very skilled printer who was entrusted by the photographer to make the print. When the photographer is honest, and indicates who actually made the print, those prints are valued less. In some cases it was only early in the photographer’s career that the photographer himself or herself would give great personal care to making the print.

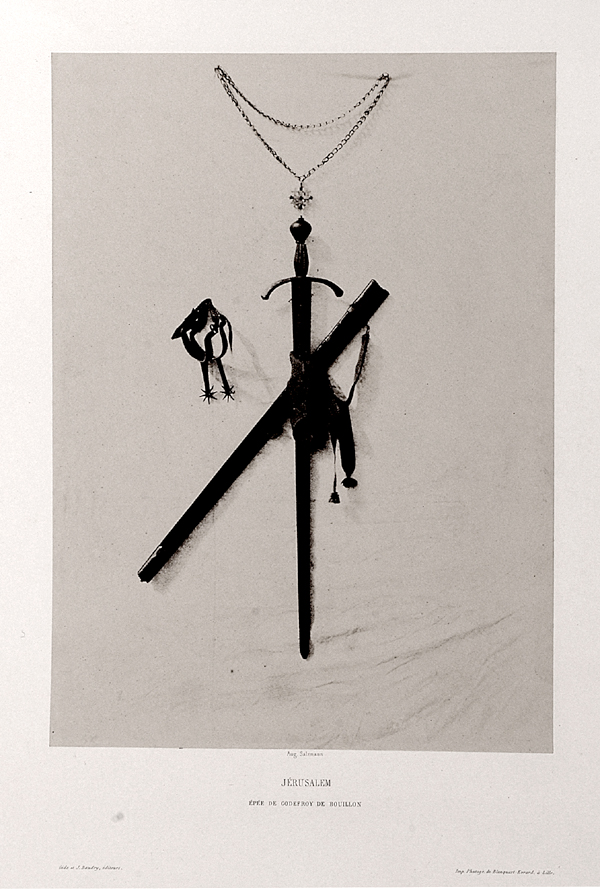

In the last few years I have paid a lot of attention to the printing history of press prints. In the last auction I had a beautiful print of the Rosenthal photograph of the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima that seemed to have been printed from the negative or a close copy negative with interesting tones and texture. I much prefer that print to later signed large exhibition prints of the same picture. I have also presented very early prints of other iconic press photographs, for example Robert Capa’s D-Day landing images. It seems that some collectors and institutions are recognizing the importance of these very first prints of iconic images.

Many photographers originally made or had made press prints of their work. They are often credited, but the prints are rarely signed. These early press prints often don’t have the character of beautiful exhibition prints on quality paper. Some are even wire photos. They are usually glossy—“ferrotyped” to make better copies– with signs of wear from use, and with interesting stamps on the back. Early ones are toned, and have a special beauty that one can come to appreciate along with the wealth of information on the verso.

It seems these prints are coming to be appreciated for the historical importance as objects. Even though they might have been originally printed in relatively large numbers, the very early editions, even wire photographs that might have been the very first, are now scarce and provide an exciting area to collect. The early works of many of the major photographers were often press prints.

Vintage “Classic” 19th and 20th century photographs by significant photographers are becoming ever more scarce. True vintage signed prints with good provenance are so expensive they are out of reach of most collectors, even those with the means to collect at high but not the highest level. Signed “printed later” prints have become mainstays of auctions. Examples of some appear in almost every general auction. I don’t mean to underestimate their appeal to collectors.

But for those who can develop the sensitivity to the character of the print, unsigned early prints that are clearly the work of the photographer, often with the photographer’s credit stamp, represent in my view an exciting collecting area.