The essential promise of the daguerreotype was truthfulness, the “mirror with a memory.” As I have immersed myself in the world of cabinet cards for the last few months, in connection with the current Be-hold auction, I often found myself in a world of contested truthfulness, a world where there was a porous border between truth and illusion. This was a concern of the age—the latter part of the 19th century and the start of the 20th. Developments in photographic practice catered to that concern.

The essential promise of the daguerreotype was truthfulness, the “mirror with a memory.” As I have immersed myself in the world of cabinet cards for the last few months, in connection with the current Be-hold auction, I often found myself in a world of contested truthfulness, a world where there was a porous border between truth and illusion. This was a concern of the age—the latter part of the 19th century and the start of the 20th. Developments in photographic practice catered to that concern.

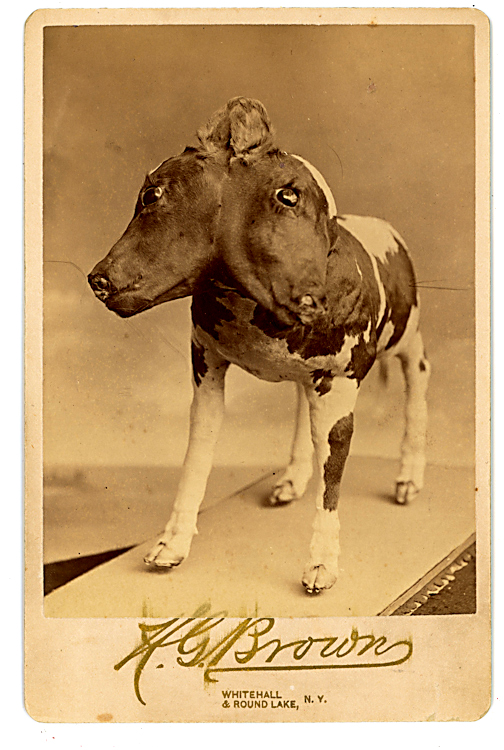

This was a world that PT. Barnum fostered and exploited already in the era of daguerreotypes and CDV’s, that fully blossomed in the cabinet card era. Crowds flocked to see in “real life” numerous types of living persons and creatures that were out of the ordinary. These included people who were shorter or taller than “normal,” thinner or fatter, with longer hair on their head or face. It especially included those who by birth or disease more seriously departed from what was usual. They were presented as real living people, but often surrounded by fictitious tales about their birth and history. Photographs often show them accompanied by “normal” family members or managers, making the photographs a mixture of verisimilitude and exaggeration or falsehood.

At the same time photographic manipulation blossomed in this period. Techniques that developed already in daguerreotypes could be achieved more easily and experimentally once printing became a separate activity from making the negative. The cabinet cards exhibit numerous examples of this.

Is this two-headed calf a freak of nature or the result of playful printing?

There are many examples of photographs using superimposition and collage. While examples of many “trick” processes can already be found in daguerreotypes, they were unique objects. So were tintypes, that often explored the same processes as cabinet cards. But the cabinet cards were made in multiple examples, from just a relatively small number by small town studios to the huge outputs of the major big city studios.

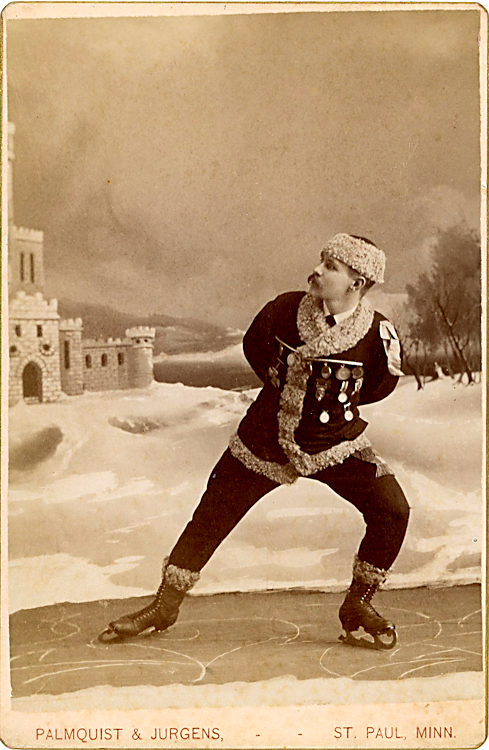

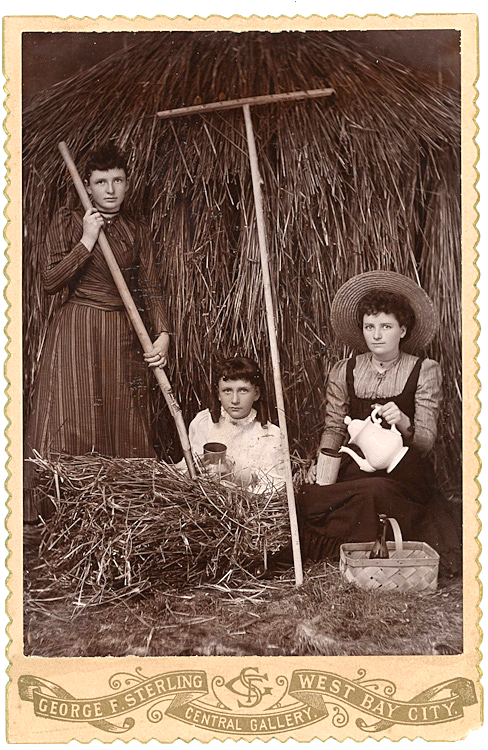

Issues of illusion were not only explored in printing, they were often part of the studio production. Studio backdrops and furniture were part of the trappings of photographs from the beginning. But even though the backdrops might show scenes, they were still part of the studio setting, and rarely was there an attempt in daguerreotypes to pretend that the studio location was somewhere else.

There are many cabinet cards in this collection where the studio is acknowledged but some kind of illusion is still established. An example is the photograph of Charles Dickens at his desk. This might seem to be in his own study, but there are indications the desk or a similar one was brought into the studio. There are many examples of occupational images where objects and trappings of the profession are set up in the studio. These don’t differ from the similar practice in daguerreotypes and CDV’s. But there are other examples where the studio is made to give the illusion of a “real” space.

An example is a cabinet card of an ice skater where the backdrop represents a somewhat realistic scene, and the floor is made up to represent ice, with even the pattern made by the blades appearing in the ice. (One wonders how the skater was able to hold his pose, or, in another subject, how bicycles were able to stand upright without any visible support.) Another photograph shows a woman and girl resting from haying. The studio is so made up with real hay that there is no clue that this wasn’t taken out in the field.

Photographs of theatrical performers represent the largest body of photographs in the collection, and are among the most numerous photographs made in this era, next to individual and family portraits. The theater itself as it developed in the West after the era of Shakespeare was a site of both reality and illusion. Like the “freaks” discussed above, the performers were real persons, but in a space of illusion. This is part of the lure of the theater. The real actors represent individuals who are not themselves in spaces that are made to seem other than the real stage. The complex fantasy involved in collecting cabinet cards of theater performers would soon be overtaken by publicity photographs of movie stars, where the “original” was not a real person but a celluloid illusion.

Photographs of theatrical performers represent the largest body of photographs in the collection, and are among the most numerous photographs made in this era, next to individual and family portraits. The theater itself as it developed in the West after the era of Shakespeare was a site of both reality and illusion. Like the “freaks” discussed above, the performers were real persons, but in a space of illusion. This is part of the lure of the theater. The real actors represent individuals who are not themselves in spaces that are made to seem other than the real stage. The complex fantasy involved in collecting cabinet cards of theater performers would soon be overtaken by publicity photographs of movie stars, where the “original” was not a real person but a celluloid illusion.

There was often a blurred line between the studio backdrop and the theater backdrop. In this masterful superimposed photograph of the actor as both Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde, it isn’t clear whether this is the backdrop of the theater where the play was performed, or the backdrop of the studio.

There was often a blurred line between the studio backdrop and the theater backdrop. In this masterful superimposed photograph of the actor as both Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde, it isn’t clear whether this is the backdrop of the theater where the play was performed, or the backdrop of the studio.

In just a few cases as represented in this collection, the outside world is presented “as it really is.” But as this example shows, the world can be used as a setting just as the studio setting can be made to represent a real outside scene. Here presumably real people, not actors, are elaborately arranged in an urban scene that has many implications. It stands between the formally arranged studio scene and the moment captured by a hand-held camera in the modern era.

………………….

These illustrations are from our October 29th auction. See www.be-hold.com

I hope this will help make it interesting to look through the material.

This is the 32nd one of my occasional Newsletters on issues about photography.

It and most of the previous ones can be found by clicking on the tab at the top our home page. You are welcome to comment on this and, in the appropriate place, on many of the previous Newsletters that can be found there. Your comments on this Newsletter can also include any issues related to Cabinet Cards and their presentation in the auction.

— Larry Gottheim