There were many fascinating responses to the last Newsletter, “What is it?”

This led me to post it on the be-hold.com website, along with a number of earlier Newsletters. I also instituted a Forum, by which readers can post comments on any of those Newsletters. I hope this will lead to interesting discussions. I have summarized some of the responses to the last Newsletter in my own posting.

The discussion in the Newsletter was directed at two issues. The first was a reading of the actual content of the scene depicted, the “picture.” The other was a consideration of what the “picture” actually was, in terms of the margin and whatever else was on the photographic sheet.

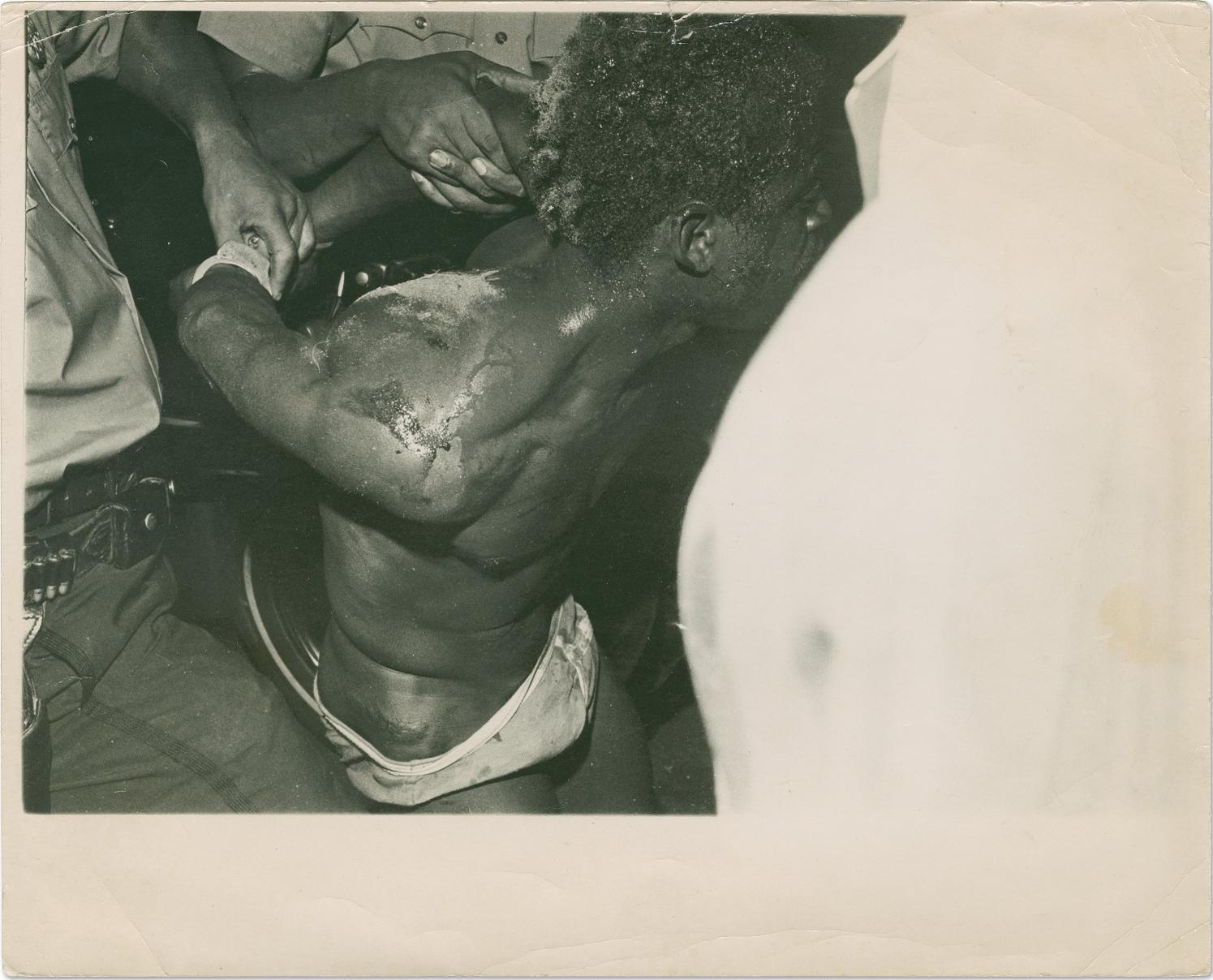

Interestingly, all of the comments were directed at a “reading” of the image. Nobody wrote about the other issue, but that is what I want to continue to pursue in this and probably the next Newsletter.

One might want to think that the actual picture is what the photographer saw in the camera’s view. As a film-maker working in 16mm, one took for granted that the framing the camera gave was unalterable With the development of 16mm optical printers a few filmmakers began to work with altering the camera’s framing, but most accepted the camera’s framing. The situation is different in the digital era, where the camera produces only a template for what the “photograph” could be.

With photographs it was different right from the start. The daguerreotypist or tintype maker could envision the mat that would eventually surround the image, and compose the image with that in mind. Early daguerreotypes with square or octagonal mats seem to have been composed expressly for the shape of the chosen mat. Southworth and Hawes often favored very thin straight mats. But mostly later daguerreotypes were less rigorously composed around the edge.

The fancy mats with curves and points along the sides blurred the straight “edge” of the image. If the mat could be opened, additional details would often be revealed that the mat obscured. Were these part of the picture or outside it? If the case and mat appear “original” then the image that appears within the mat is usually accepted as the “picture”, and the other details are “behind the scenes.” A not uncommon instance of this is a daguerreotype of a child, with the mother holding the child, hidden behind the mat.

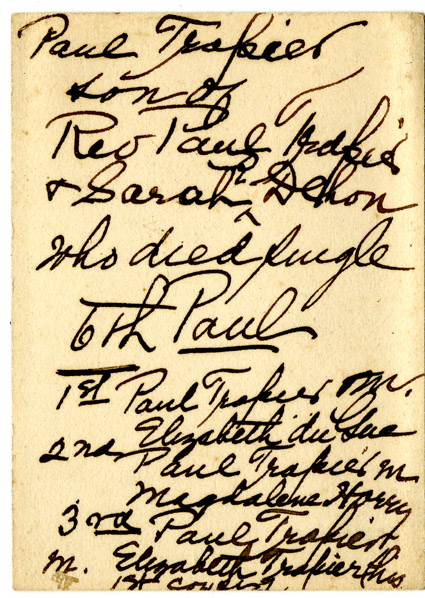

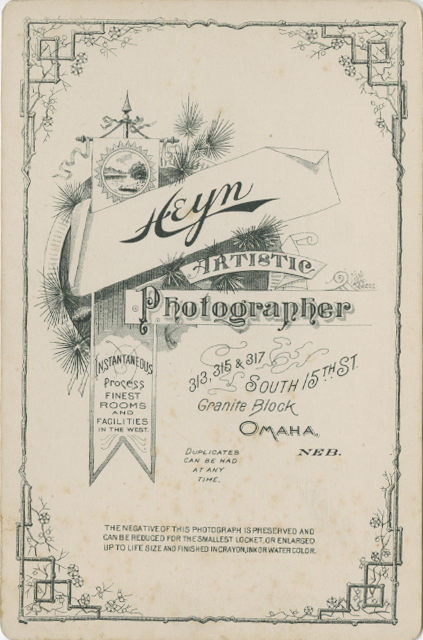

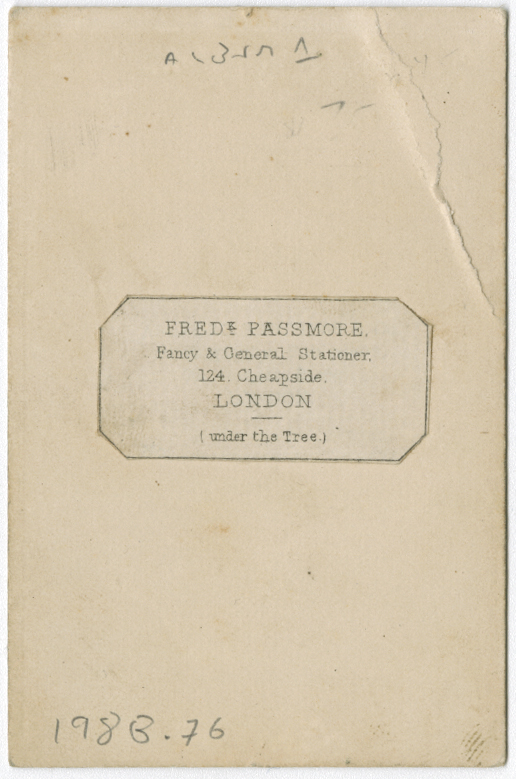

19th-century paper photographs fall into two general sizes. The smaller formats were presented on mounts, often decorated and bearing printed information. While the photograph mounted on the card could be seen as distinct from the mount, the mount and the card are today mostly considered to be one object, married forever. Collectors savor even minute variations of the mount as different objects.

Few would think of removing an albumen print from a carte-de-visite and giving it a different presentation. The “photographic object” is the entire mount, including the edges and the verso, as well as what is on it. Yet oddly, in the CDV era, most CDV’s were inserted into albums that obscured the edges and the verso. Indeed the compartments for the CDV’s in albums were so tight that many CDV’s had their edges and corners trimmed to allow for easier insertion into the album. It is only in recent years that it has been more common to place CDV’s’ in relatively safe sleeves, and collectors make a fetish out of the original edges.

In the current exhibit of Civil War photography at the Metropolitan Museum, CDV’s are presented on simple stands that allow the full object, front and back, to be seen. For some this seems a brilliant solution, only right. For others, used to looking at albums, it seems strange.

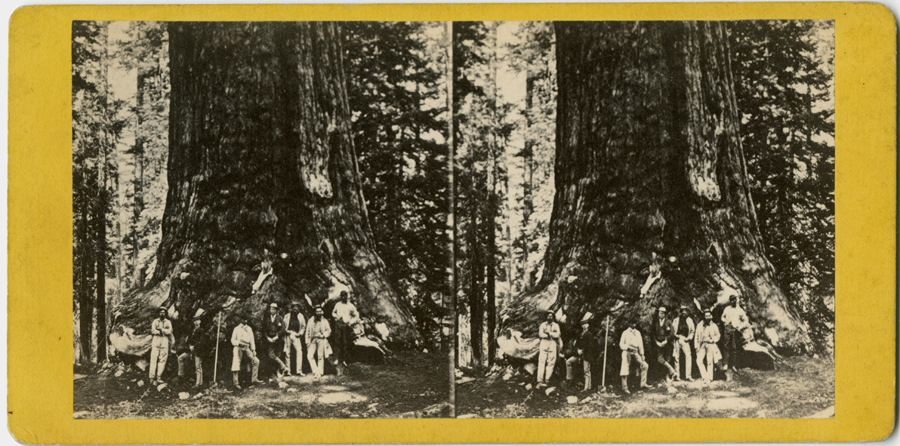

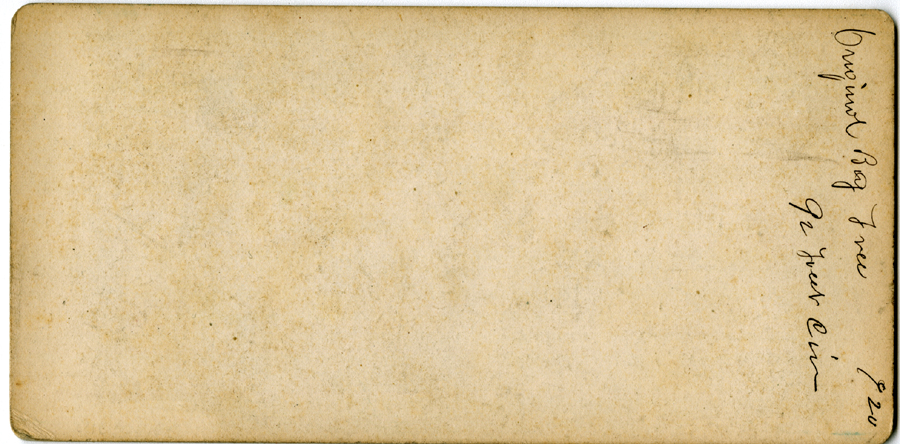

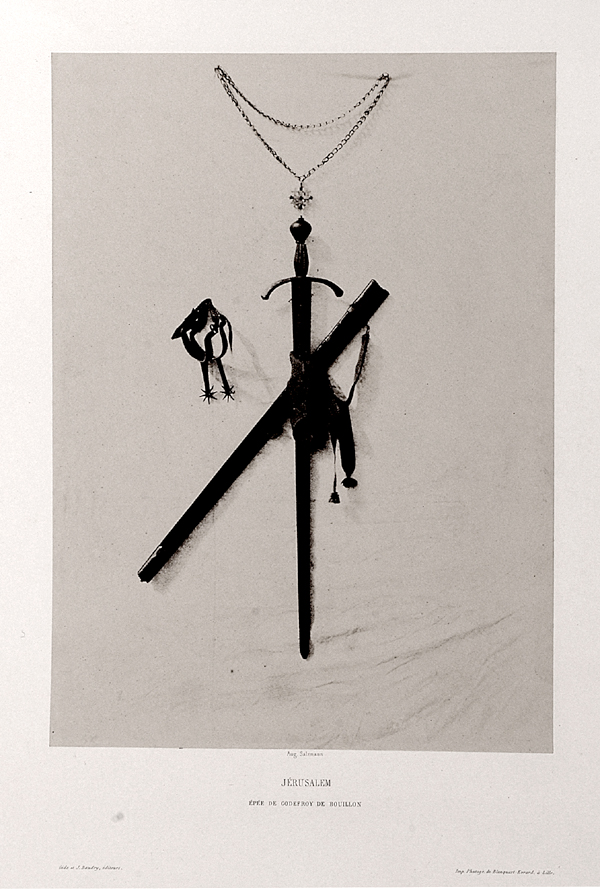

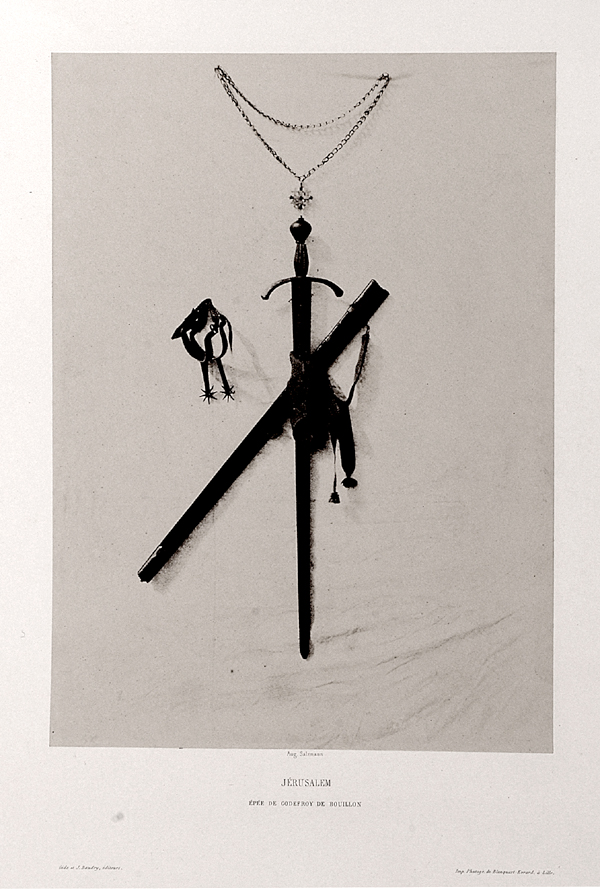

At the other end of the size scale, albumen and salt prints were often mounted by the photographer or publisher on very large mounts. These often had letterpress titles, photographer identification, blindstamps and other markings. If these were in turn placed in portfolios or large albums, the entire mount was meant to be seen. The photograph and its mount were a single “photographic object.”

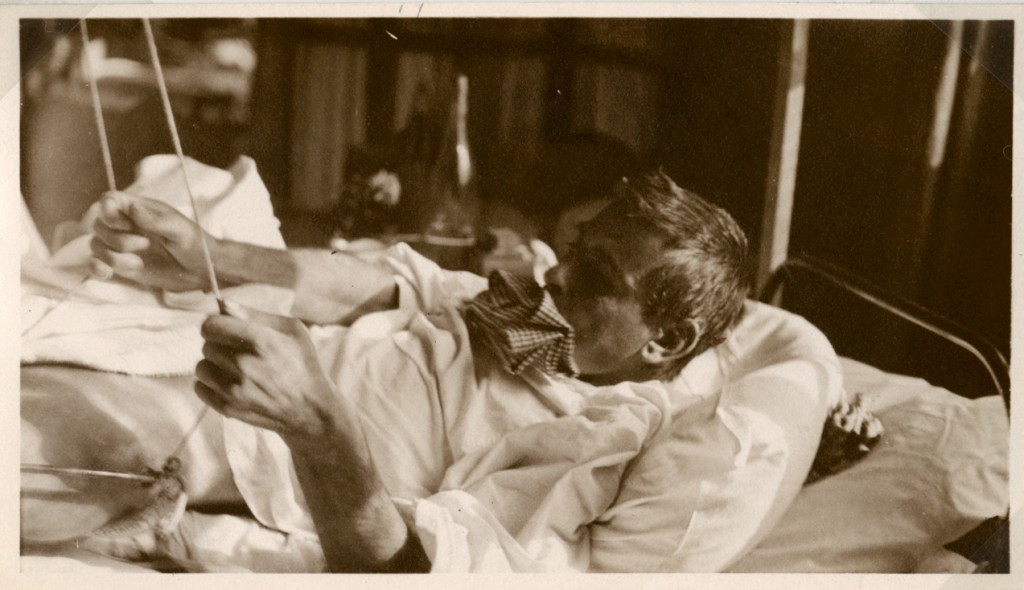

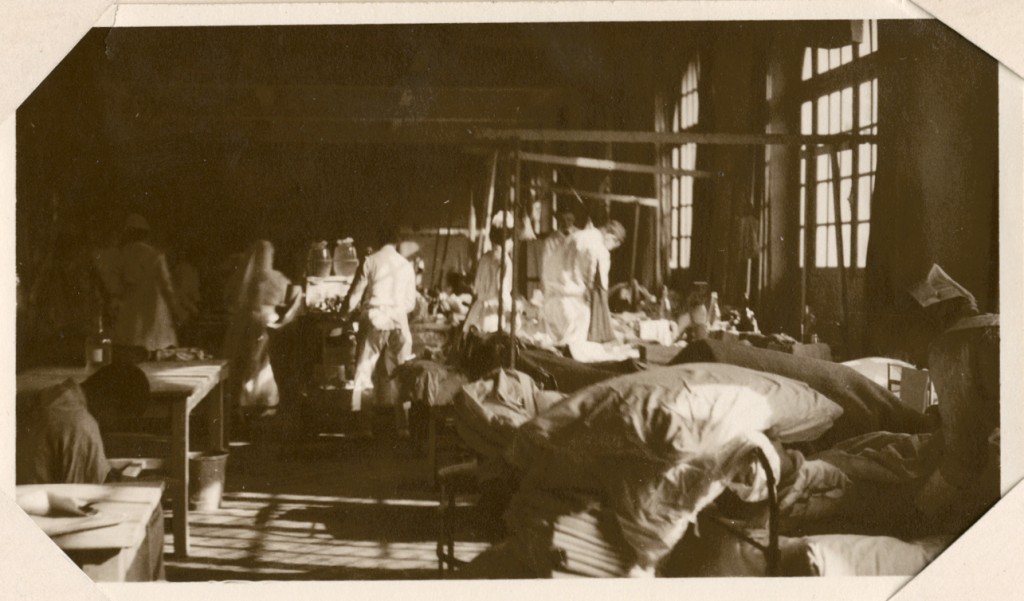

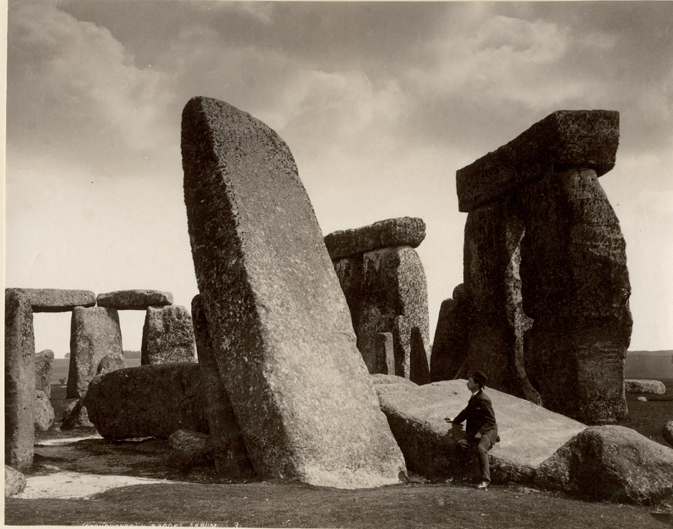

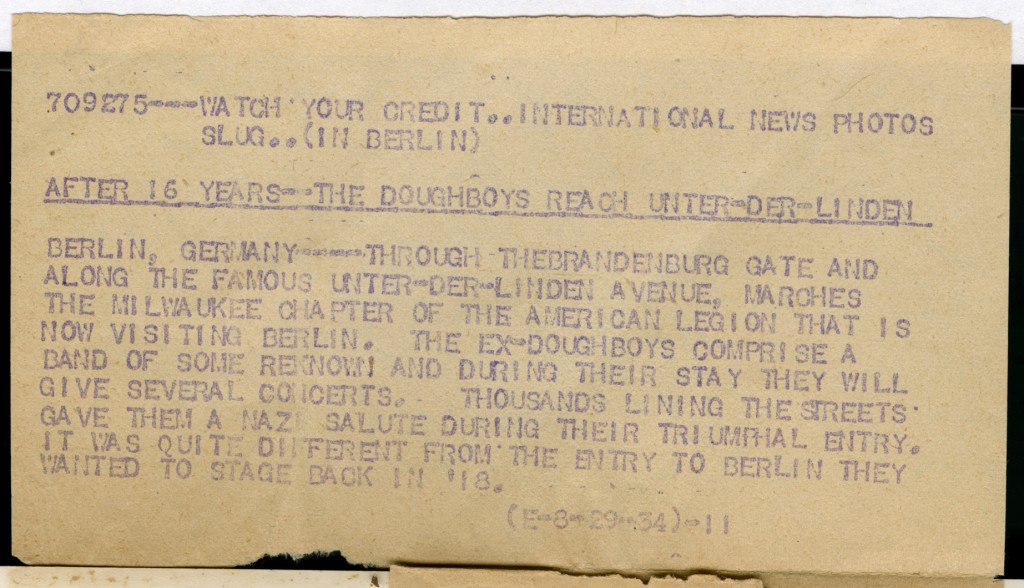

Here is an example of that:

Indeed this presentation also dictated an order in which the images would be seen. The “Hand and the Wall” issue discussed in some of the earlier Newsletters [See Newsletter 4, available on the be-hold.com home page.] was directed at the issue of small-scale photographs, held in the hand, vs. larger ones meant to be hung on the wall. I wasn’t thinking then about these large-scale photographs that were also originally meant to be turned by hand in larger albums or portfolios.

As photograph collecting expanded by both institutions and private collectors, several factors contributed to the dominance of the wall. The original albums and portfolios were scarce and increasingly expensive, so few could manage to acquire complete ones. Those fortunate enough to own them would have a problem to display them. This was especially true for institutions, that had a mission to bring in visitors, and to make their holdings available to the public.

Portfolios and albums were broken up and individual “photographic objects” would be purchased or displayed individually on the wall..

Sometimes curators and collectors who make a fetish out of preserving intact albums that were assembled by patrons rather than photographers (such as travel albums that were assembled from the traveler’s choice of prints available in a shop during a world tour) don’t hesitate to display a single page or sheet from an original album or portfolio.

There is certainly a question about presenting a single page separated from its original context. But beyond this is the question about how to present it, if it is to be matted and framed to put on a wall (where it will be seen vertical to the viewer, rather than down on a table.) Following a trend used in presenting 20th-century photographs, these objects are often matted so that only the photographically printed image is seen in the window of the mat (I’m assuming the mat is not obscuring part of the image, though this is often not the case..) So the picture is floating in a flat sea of mat board, unmoored from any title, number, name or even signature that was part of the original object. In some cases holes are cut into the mat to show some element that is deemed worth showing—little islands far from the shores of the image itself.

Sometimes the scale of the mat has nothing at all to do with the scale of the original object, as the case of small images and even CDV’s mounted in windows cut into huge oversized mounts.

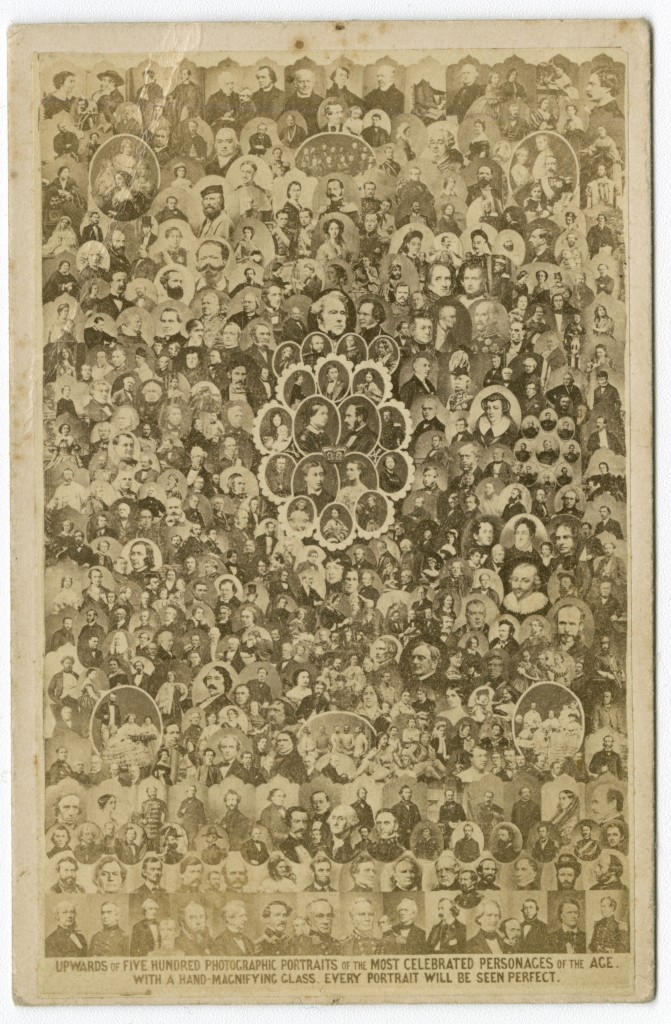

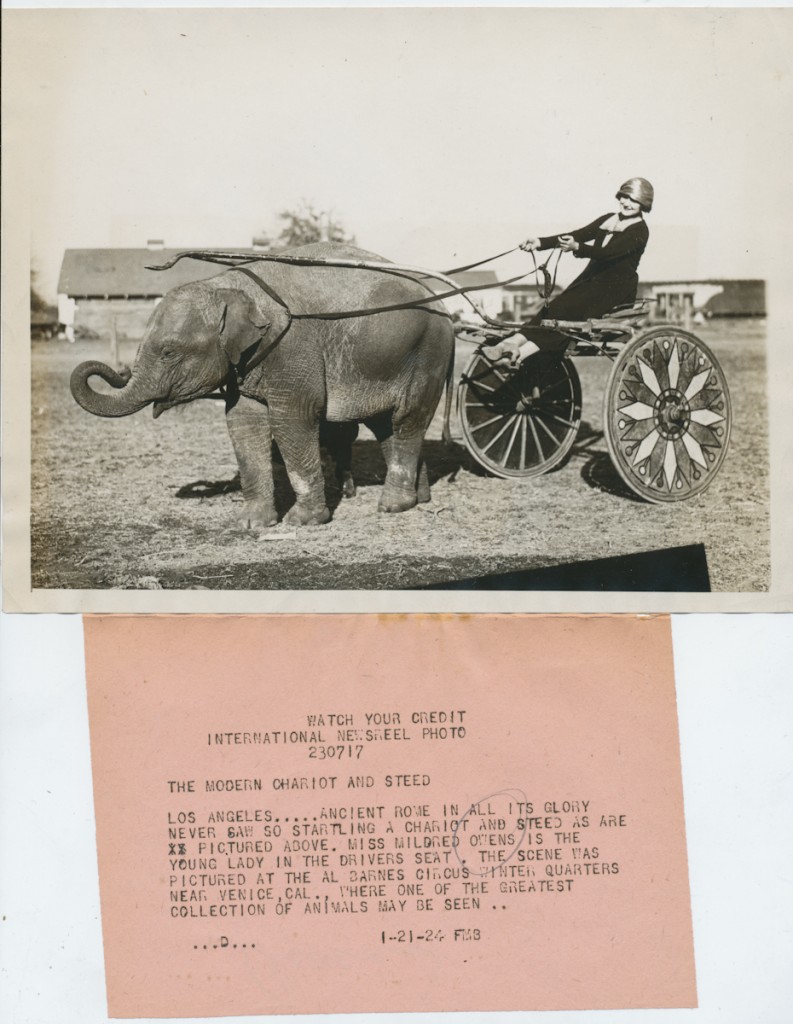

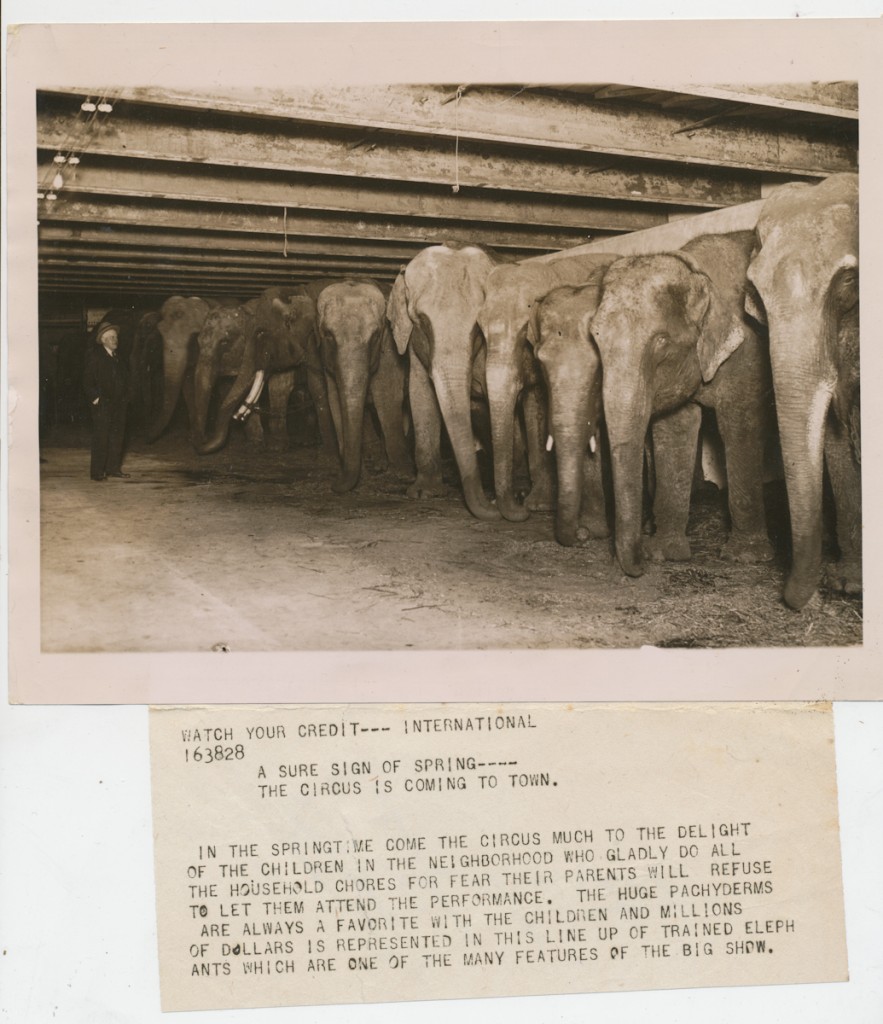

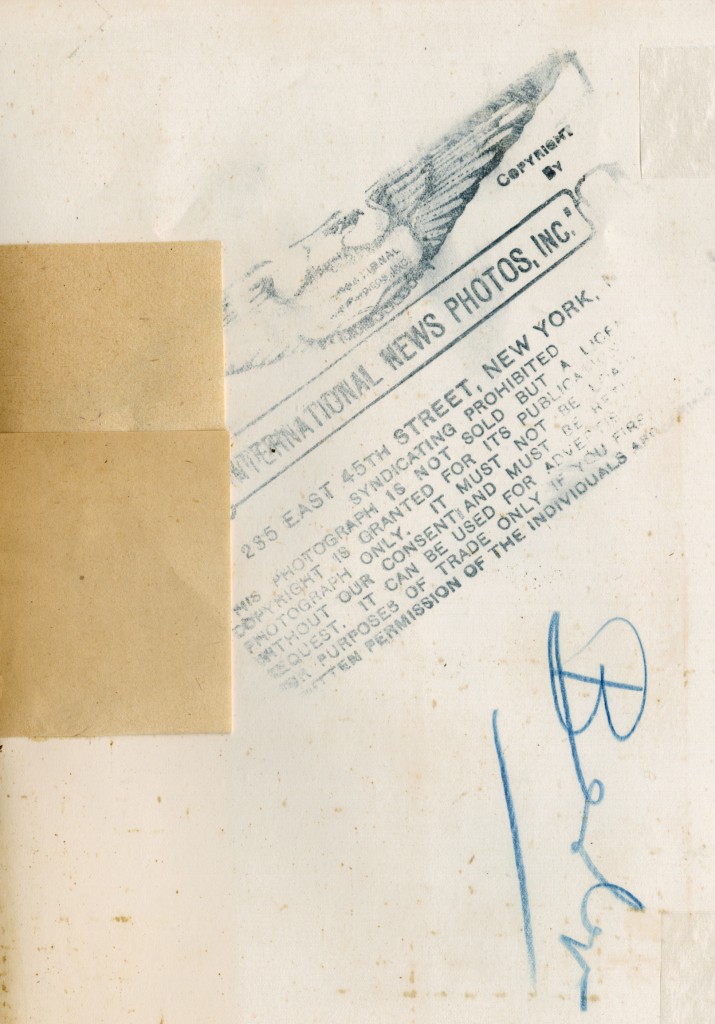

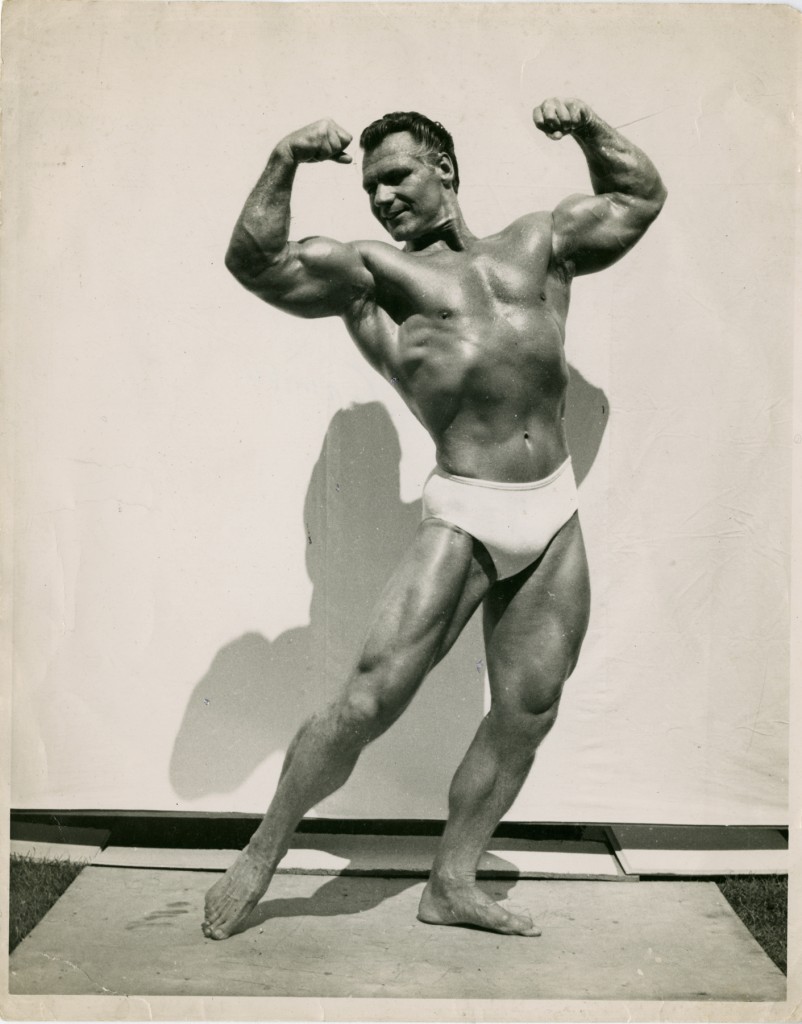

These issues don’t only apply to 19th century photographs on mounts that are part of the photographic object prepared by the photographer. 20th- Century photographers had many choices in how to print their images on the photographic paper they selected. They could, for example, print their image edge-to-edge on the existing paper. Or they could print the image on the full sheet of paper, and then crop it to the edge of the image. Or, as is often the case, they could print the image onto the paper leaving a margin of even or uneven width. Many photographs are found with many deep margins at the bottom or one or both sides.

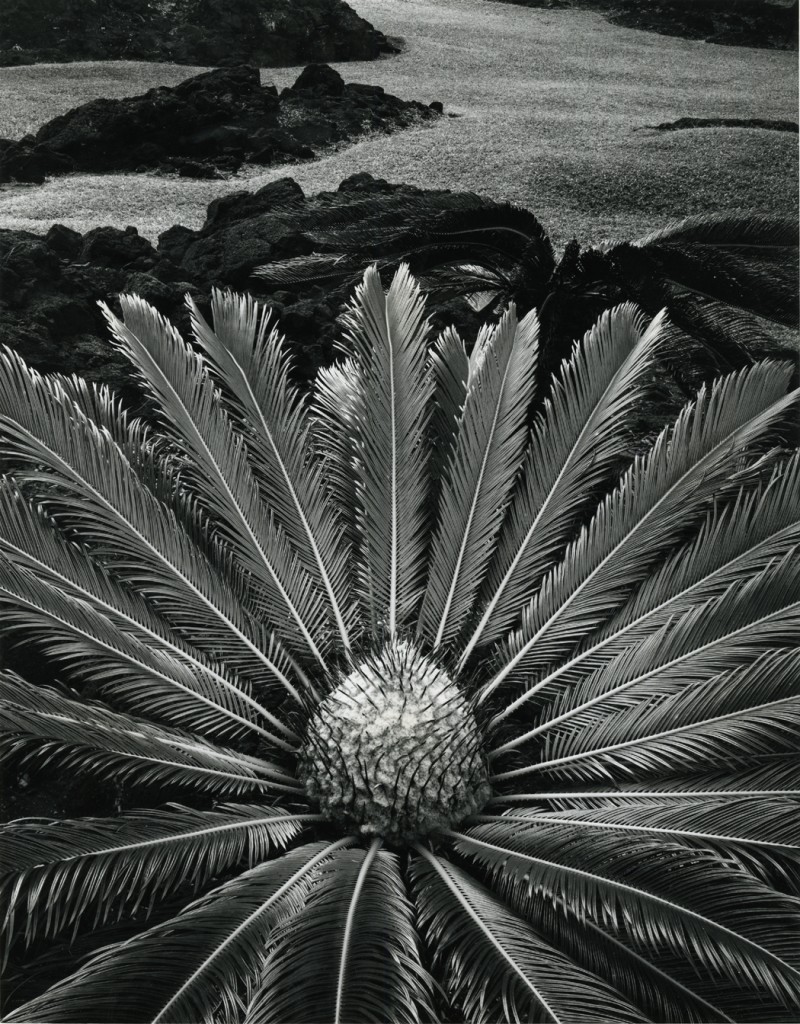

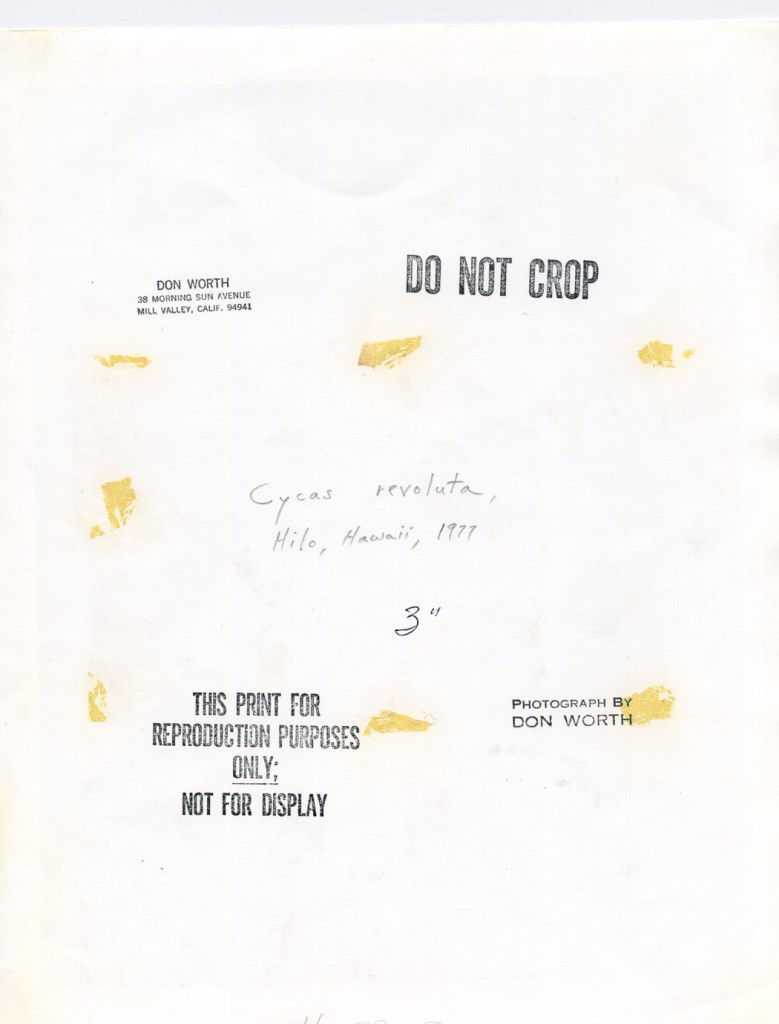

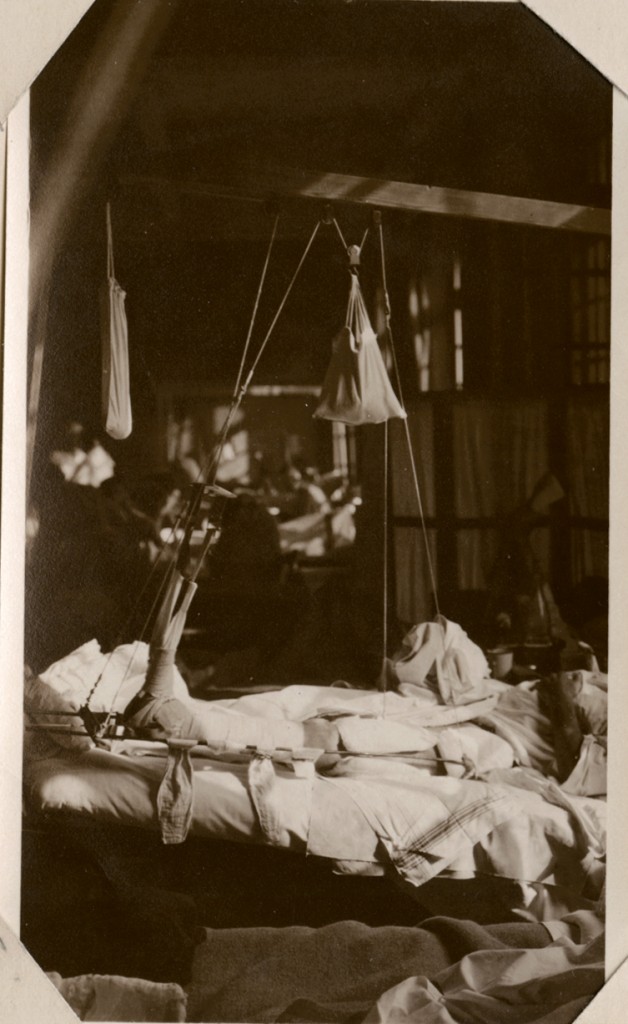

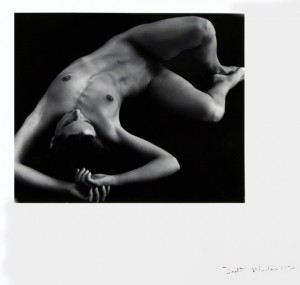

For instance:

Photographers could also mount their image directly on mounts, and here they had similar choices. They could mount it with symmetrical or unsymmetrical borders. The photographer could decide whether and where to place a signature, title, date and other information, whether the borders or margins were regular or irregular. If some of the information was “far” from the image, this suggests the photographer wanted the entire mat or margin area to be part of the presentation.

Dealers, collectors, gallerists and curators should be mindful of the choices they are making when matting and framing. These very often go against what appears to have been the intention of the photographer as to what constitutes the “photographic object.”

Far from exhausting this subject, I keep thinking about more related issues that I want to explore in the next Newsletter. Meanwhile I invite you to leave comments on this and previous Newsletters by visiting our website, here.

……………………

I’m working on several bodies of material for the Fall Be-hold auction. Let me know if you have exciting material to propose for consignment.